Humans have been drawn to dance for thousands of years as a way to communicate—to express emotion, to display status—though styles and purposes have evolved and expanded substantially over time. The roots of social dance, as we know it, lie in medieval court dancing, which later evolved to coordinated couples’ dances and eventually ballroom-style dances.

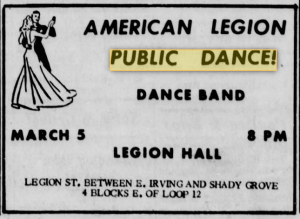

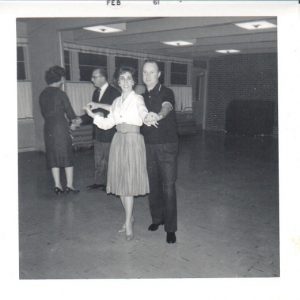

During the early-mid 20th century and beyond, but particularly 1920s-1940s, dancing was a staple in adolescent social circles and adult nightlife in the United States. By this time, some traditional dances (foxtrot, two-step, waltz, etc.) were paired with contemporary music, and thus rebranded. Perhaps most notably, dances began to wane in formality compared to the rigid etiquette followed in the 18th & 19th centuries, though many rules of decorum prevailed. Social groups or individuals organized dance parties or dances were held in public ballrooms, dance halls, or private clubs. Dances could be combined with a dinner or banquet, a benefit or gala, coming-of-age ceremony—such as a bar-mitzvah, sweet-sixteen, or cotillion—or be purely social in nature.

Dances, both public and private, were often preceded by an invitation or dance card—dance halls were an exception. Invitations and cards served a dual purpose – to identify organizers, purpose of the event, dances to be performed, and to act as a souvenir of the occasion. It was not uncommon for there to be a space, or several, for ladies to list their date or dance partners. Advertisements in local newspapers also occurred for public dances. In this exhibit, you will see dance cards, invitations, advertisements, photographs and programs from dances and community gatherings where dance occurred from several collections in the DJHS Archive.

Nowadays, dances and galas still occur, though they often have a different look and feel from the traditional dance parties and dinner-dances of the early-mid 20th century. This exhibit aims to explore the long history of social dances and galas in the Dallas Jewish community.

***Click on an image to expand each gallery***

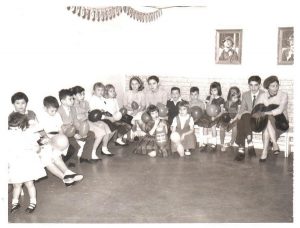

Youth and Young Adult Formal & Semi-formals

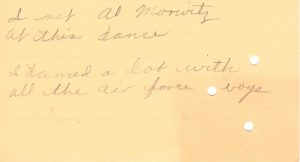

Armed Services Dance, 1950s – Jewish Welfare Fund Collection

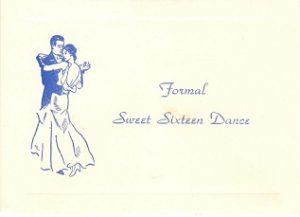

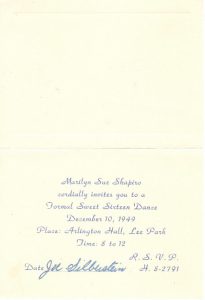

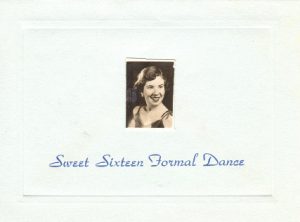

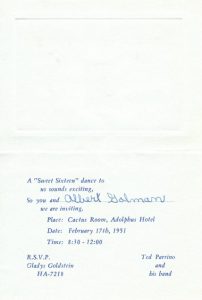

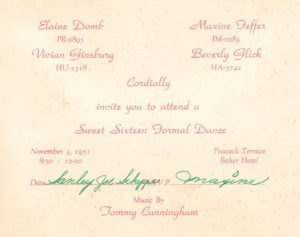

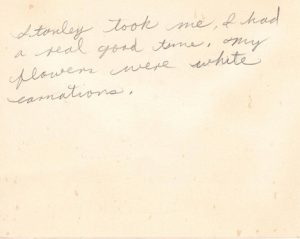

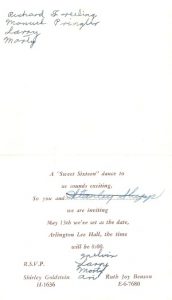

Sweet Sixteens in Jewish Dallas

While bar/bat mitzvahs and confirmations remain long-standing traditions and milestones in Dallas Jewish adolescence, Sweet Sixteen dances also held the spotlight in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The Madelyn Schepps Collection here at DJHS offers many outstanding examples of invitations from formal Sweet Sixteen Dances held from 1949-1951. There are also examples of purely social dances held by young ladies in the Jewish community. Some invitations include an assigned date, and on others Madelyn jotted personal notes related to the evening.

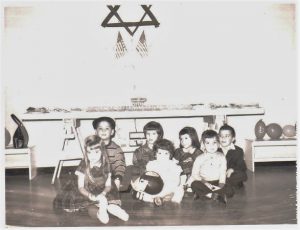

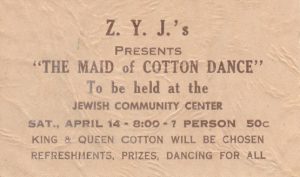

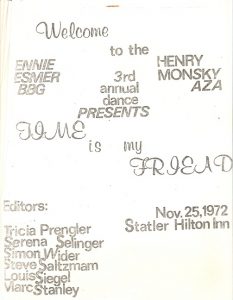

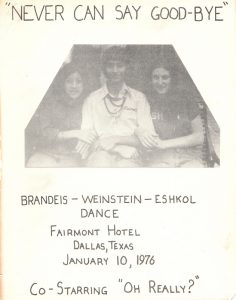

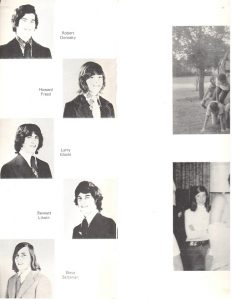

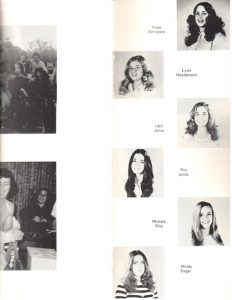

Jewish Youth and Young Adult Organization Dances

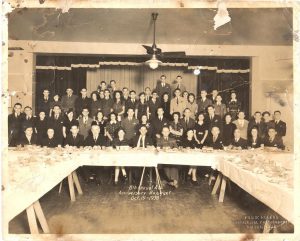

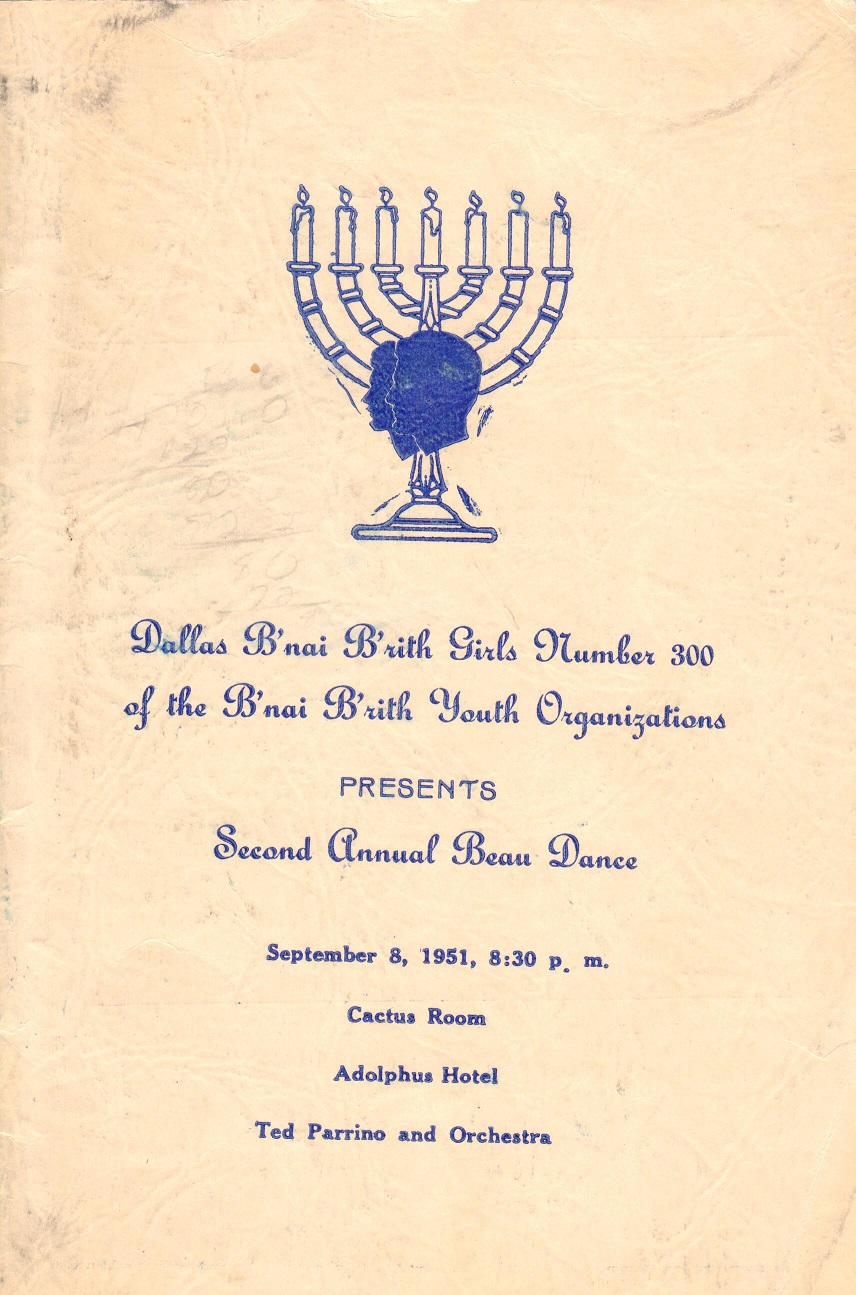

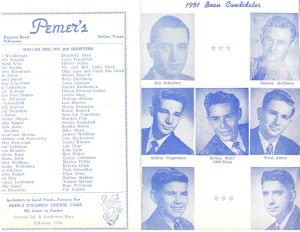

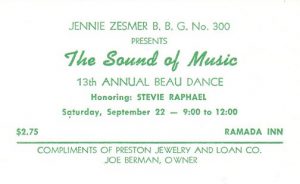

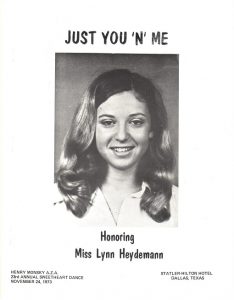

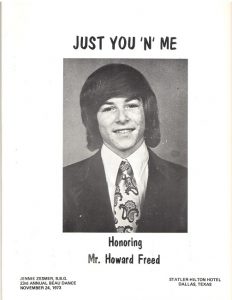

Aleph Zadik Aleph was founded in 1924 as a male-only Jewish youth organization. They were adopted by B’nai B’rith soon after and gained a strong presence in Dallas. In the 1940s, after B’nai B’rith Girls was formed, both organizations operated under the umbrella of B’nai B’rith Youth Organization (BBYO).

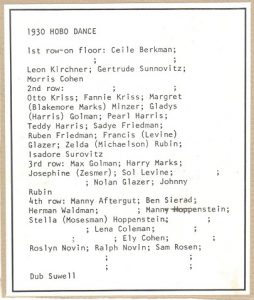

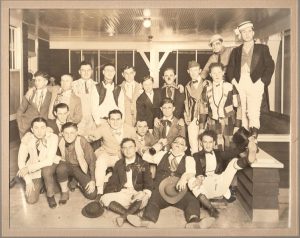

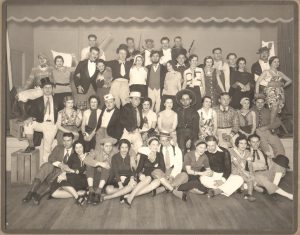

AZA held youth social dances over many decades, including Hobo Dances (predominately in the 1930s) and Sweetheart Dances, which were later held in conjunction with BBG Beau dances, annually. Dances often occurred in conjunction with annual banquets or ceremonies, as well. In some BBYO regions, Sweetheart/Beau dances still occur. However, in the North Texas Oklahoma Region, this event has evolved into more of a formal ceremony/reception called Walkdown. Morton Lewis AZA #135, a local Dallas chapter, still holds an annual dance/fundraiser and there are often dance parties during BBYO camps or conventions.

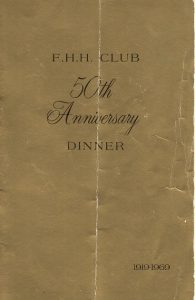

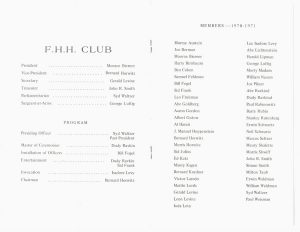

Forty Hungry Hebrews was a Jewish men’s fraternal organization and social club in Dallas in the 1930s thru the 1950s. They sponsored community sporting events and other gatherings.

Other Jewish youth and young adult organizations like AODA and ZYJ also held dances and parties. Notably, AZA and FHH both held several social costume dances, called Hobo Dances.

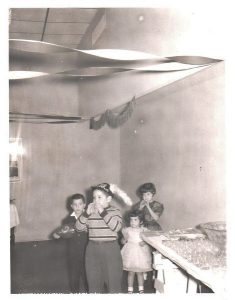

Hobo Dances

There are a few different theories as to how the term “Hobo” came about. One suggests that “Hobo” is a contraction derived from the term “hoe boys,” which referred to young men who would do farm work or similar labor in order to negotiate wages or food for a period of time [the feminization of the term is “Hogi,” (i.e. hoe girl)]. Hobos would generally camp in groups and travel from place to place, via train, when work dwindled. This trend of migrant laborers is often aligned with the Great Depression, but it extends from the late 1800s to the early 1950s – spanning a period of immense growth in the railroad system, which provided greater freedom to those seeking a nomadic lifestyle, and multiple eras of socio-economic hardship including the Depression and the deluge of American soldiers returning home to limited job prospects and alienation from average daily life following World War II. The combination created two distinct types of Hobos – those who traveled for exhilaration and freedom, and those who traveled out of necessity.

The image became so entrenched in popular culture, the trope was adopted in games and movies, and as a dance theme by youth and young adult social groups – both Jewish and secular – in the 1920s through the 1950s. The DJHS collection contains photographs from Hobo Dances sponsored by Aleph Zadik Aleph (AZA) and Forty Hungry Hebrews (FHH) from 1932-1938. Newspaper articles from Maine, New York, Ohio, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, Kentucky, Missouri, Texas, Oklahoma, Montana, and Oregon dating from the mid-1920s to 1960s identify a trend of Hobo dances extending far beyond both Dallas and the Jewish community. But why? What intrigued these kids to the point of celebrating as Hobos?

An article from Eastern Progress in Richmond, Kentucky on March 19, 1951, states: “Ties and tails are definitely out, as one can gather from the name. If you want to be a big hit, just wear your oldest and shabbiest rags and use your own judgment about shoes! The Hobo get-together is always one of the merriest events on our campus.” Ladies and gents were referred to as “drags” and “stags.” This particular dance was held by the KYMA Club at Eastern Kentucky University.

A common thread among various Hobo dances is the contrast of attire and mood compared to the traditional black-tie or cocktail theme of dances during this era—feeding into the stereotype of the Hobo as dirty, smelly, and lazy. However, that is somewhat of a misconception. The first National Hobo Convention was held in 1900; it manifested as a means to distinguish Hobos as a responsible, nomadic subculture that valued work and assisting others, a clear distinction from the bums and tramps that perpetuated the stereotype. Similarly, Grinnell College – A Liberal Arts College in Grinnell, Iowa, with an extensive resource related to Hobo etymology provided by their Sociology Department – indicates that many Hobos valued personal hygiene.

The dances also embraced the free-spirited mentality that diehard Hobos were known to possess. They were an opportunity to let loose a little and step outside the familiar decorum of the communities that hosted these gatherings. It was also an occasion for some showmanship and frivolity, which was supported by the 1930s dance renaissance that brought the Jazz Age Swing, Lindy Hop, and other active dance styles to the scene.

Perhaps most intriguing about the concept of the Hobo is the distinction of work vs. wander. Contributing writers at The Globe and Grinnell College differentiate Hobos from “tramps” or “bums,” as tramps and bums more often wander, or linger, seeking handouts, rather than compensation for work. Although, “tramp,” was also used to refer to laborers who would seek work by foot before it evolved to mean non-working wanderer. Grinnell further elucidates, citing the autobiography of famed Hobo Charlie Fox (1989) and Graham Raulerson’s, The hobo in American musical culture (2011), that “work is anything that helps, ‘the material, emotional, or intellectual welfare of oneself or others…There is an element of social responsibility in this idea of work.’” While the national trend of Hobo Dances may have been some superficial fun for those participating, it is the spiritual edge – the social responsibility – of the Hobo lifestyle that creates an unusually organic connection with the Jewish community.

Rabbi Toby Manewith was quoted, “our decision to ignore or respond to members of our communities who are in danger determine the justice and morality of our society.” A pillar of Judaism is to care for community members who are not able to care for themselves, and caring can take many forms, whether that be mitzvot, a favor to a friend or neighbor, or a donation to a community organization. So, even though the structure and many philosophies of the Jewish community may differ from those of Hobos, they share a common root in the betterment of community, and ultimately self, by acting in the interest of others.

You will notice that there are duplicate images in the photo gallery – this is intentional to show that multiple individuals, families, and groups, maintained their connection to these dances for several decades.

Public Dances and Galas

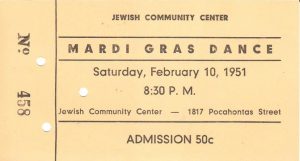

Large dance parties in public ballrooms, public and private clubs, and dance halls were common in Jewish Dallas in the early-mid 1900s. The Columbian Club, a private Jewish social club once located in South Dallas, held many ticketed dances for its members, especially in the early 1900s and 1920s. Public ballrooms like the Baker Hotel’s Crystal Ballroom held many ticketed dances for the wider community, as well.

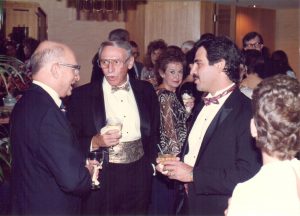

Over the years, traditional ticketed social dances have waned in popularity, but social functions and benefits that include entertainment such as dancing have sustained. By definition, a Gala is a social gathering with special entertainment and usually intended to raise money for a benefit or cause.

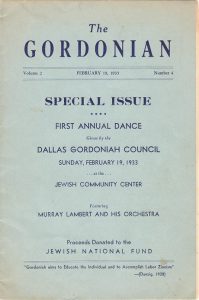

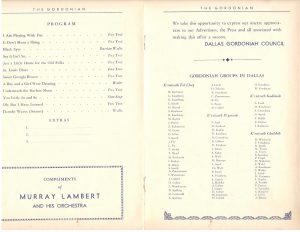

Not surprisingly, the Jewish Community Center, in its many iterations, has been host and home to countless dances, parties, and galas over several decades – from a JNF Gala held at the Jewish Community Center in South Dallas in 1933 (and likely others before), to the most recent in-person be. Event, held in 2019.

Jewish-owned dance halls were also prevalent and offered a more casual atmosphere to participate in social dance.

Dime-a-Dance Halls

Dance halls, or night clubs, began gaining popularity in the early 1900s, offering a venue for live music, drink, and dance. Overall, there were two types: dancehalls where you could take a date, and dancehalls you could go to dance when you didn’t have a date, also known as dime-a-dance halls. “Dime” could refer to cost of admission to a dance or establishment, though generally, “dime” referred to the cost of individual dances with “taxi-dancers” in dance halls and private clubs. The private clubs popped up in response to prohibition and sometimes took on the façade of a dancing school to evade authorities. Sometimes dances featured bands called “grind-groups” or music was provided by nickelodeons – jukeboxes that took nickels.

Dime-a-Dance Halls, also known as Taxi-Dance Halls gained popularity leading up to and during the 1920s when red-light-type establishments were closed due to sweeping reform policies across the country. The concept invited male patrons to pay a dime, ten cents, for each dance with an employed female dancer in her late teens to late twenties. Dancers received a cut of each ticket they received at the end of the night. There were clubs with flipped roles, but they were fewer in number and tended to be in larger cities. Overall, Dime-a-Dance establishments developed a reputation for crude behavior and indiscretion. Patrons were often working or lower-middle class, but otherwise varied widely in age and background. The clubs allowed a sense of freedom, interaction, companionship, enthusiasm, and fun without obligation, responsibility, or judgement. There were a few dime-a-dance clubs in Dallas, including the Triangle Club, opened by Abe Weinstein at 1322 ½ Commerce Street in 1932, and the Wonder Bar, which was above the old gas company building on the 2400 block of Commerce Street, owned by Sam Goldberg and Joe Utay. Dallas passed a city ordinance in 1938 banning dime-a-dance venues in the city.

Wonder Bar Dime-a-Dance Girls with Mrs. Sam Goldberg and Joe Utay, Wonder Bar, 1935

Tripping into the Future

In these socially-distanced times, even the thought of participating in social dance feels but a memory, if not entirely wrong, as evidenced by the many gatherings negatively reported in the news currently. However, given the variety of dances, galas, and parties, over a period of nearly one hundred years, portrayed in this exhibit, we will return to an era of gathering, of touch, and of dance partners. Dances and related get-togethers are so engrained in the social fabric of U.S. culture that we must believe hope is on the horizon and that, before too long, we will be able to trip the light fantastic together, safely, again as we have following world wars, past pandemics, and periods of economic hardship. Thankfully, technology provides an edge over our ancestors, offering the opportunity to participate, assist, and dance together, albeit virtually.