Isidore Zesmer, 1911

It is with great excitement that we present the Isidore Zesmer Collection! This collection has been a part of the Dallas Jewish Historical Society Archive for many years–processed and available for research, but without the supplemental documentation that allows greater accessibility to the community.

This Summer, we were fortunate to receive the assistance of an intern, Cyna Sabu, through the annual Jewish Family Service Klein Internship program. Her project focused on the Isidore Zesmer Collection, with the goal of improving access while learning how to utilize primary source documents for research. With Cyna’s help (180 hours worth), we now have a complete finding aid, over 1100 digitized photographs, and a summary of Isidore Zesmer’s life, work, and contributions to the Jewish community. Below you will find Cyna’s essay, the last piece of the puzzle that pulls all of her hard work together. Thank you, Cyna!

Follow this link to visit our Digital Archive and view the finding aid for this collection.

Fun Fact: Throughout primary source documents in the Isidore Zesmer Collection and various publications you will see varied permutations of Zesmer’s name, including Isadore, Isador, Isidor, Isidore, I., and Ike. We have chosen to use “Isidore” in naming the collection, as well as in future publications because that is what is found on his grave marker in Congregation Shearith Israel Cemetry.

Jessica Schneider

Archivist and Volunteer Director

Influential Figures of Jewish Dallas: Isidore Zesmer

Introduction

Isidore Zesmer was an influential businessman in Dallas, TX. He was an advocate for the first Jewish school, Hebrew School of Dallas, in the Dallas area. He was involved with organizations such as Congregation Shearith Israel, Jonathan Club, Young Men’s Hebrew Association, Jewish Welfare Federation, Dallas Committee for the Israel Bonds, Zionist Organization of America, Boy Scouts of America, American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science, and Texas Zionist Association. Zesmer was known to many as a philanthropist who stood up for education and financially contributed to causes and Jewish organizations, in Dallas and globally.

Early Life and Marriage

Zesmer was born in Kritinga, Lithuania on July 9, 1888, to Joseph Zesmer and his wife, Sophia Guttmann-Zesmer. Joseph Zesmer died when Isidore was only 2 years old. His mother later remarried a sibling of his uncle A. Toplitz and they had a daughter, Isidore’s half-sister, Sophie Ospovat. At the tender age of 10, he was given his first job collecting pennies for the poor. In 1902, under the invitation of A. Toplitz, his uncle who was a dry goods merchant, Zesmer immigrated to Henderson, Texas to finish his education. When he was fifteen, in 1907, he peddled dry goods from a horse-drawn wagon in the Lufkin-vicinity of East Texas. He became the manager of a retail store in Liberty, TX at the age of 20. A couple of years after being the manager of a retail store, he took over Grand Leader Dry Goods in Denton, TX, where he later became part owner.

In 1912, Zesmer moved to Dallas and started a retail shoe business in a second-story location where A. Harris department store stood. In 1915, he married Jennie Hesselson of Dallas, and telegrams, dated January 5 & 6, 1915, were sent to congratulate the couple for their wedding. They had three children: Mrs. J. Rothschild of Dallas (Miriam Zesmer), Mrs. Sol Levine of Dallas (Josephine Zesmer), and David Zesmer of New York City. On November 30, 1919, he earned a Stock Certificate from BARR-MANN Shirt Co. in Dallas for owning 41 shares of the capital stock. He was also a co-chairman of the Dallas Committee for the Bonds, and an active salesman of the Bonds in the Southwest.

Commitments to the Jewish Community

On March 1st, 1925, Isidore Zesmer became the President of Congregation Shearith Israel. As President of Shearith Israel, he fought for better education at the synagogue, by sending out a letter to the board of directors of the synagogue stating that there should be education for kids in the Jewish community, and helped increase membership by 100 members. From May 11 to December 8, 1925, Zesmer was embroiled in a scandal related to Shearith Israel board elections. Zesmer had appointed a few individuals to various offices and leadership positions. Subsequently, Mrs. L.B. Rosenburg, President of the Ladies Auxiliary of Congregation Shearith Israel at that time, wrote Zesmer a letter saying that the elections were held illegally according to the synagogue’s bylaws and parliamentary rules. After receiving the letter, Zesmer sent a letter to the board protesting that the elections were held on unfair advantages, but his letter got rejected because he did not have clear reasoning for his protest.

Zesmer funded $500, today worth $8700, toward the building of the Hebrew School of Dallas on December 18, 1940, and acted as treasurer and finance director for 18 years. He contributed to the school’s creation by raising funds for the school to run smoothly. He also held positions within the school committee such as being an officer for the Education Committee in 1940, Secretary of the Project Committee, and officer in the Solicitation Committee. Though he held several positions, he mainly focused on the finances of the school. In 1940, he addressed the matter of a budget deficit to the point where the Hebrew School of Dallas could not keep running. He said that people needed to start funding more money for the school to run. It turned out that several people in the Jewish community donated money to keep the school open. Through supporting the Hebrew School of Dallas, he spread the message of education for the Jewish community of Dallas.

In 1947, Zesmer donated $500,000, today worth $5.6 million, toward the Million Dollar Campaign, a fundraising drive by the Jewish Welfare Federation, organized to raise $500,000,000 necessary for national security to protect the citizens of Palestine. Though Zesmer made the largest contribution to the Million Dollar Campaign, Sam Bloom, a member of the Federation Campaign, was incorrectly attributed as the main sponsor of the campaign and took the credit away from Zesmer. On May 1, 1947, Henry S. Jacobus sent a letter to Zesmer acknowledging his generous contribution to the campaign. Another letter on June 2, 1947 was sent from Bloom to Zesmer, stating that Bloom regretted taking Zesmer’s credit in ending the Million Dollar Campaign. Though people appreciated Bloom for assisting in reaching the campaign’s goal, they did realize that it was Zesmer’s hard work that contributed most to the Million Dollar Campaign.

Job as Air Raid Warden and Business

Apart from being a community leader, Mr. Zesmer also acted as Air Raid Warden in 1942. An Air Raid Warden was an appointed volunteer who made sure that every citizen in his/her assigned sector was protected from air attacks. The duty of an Air Raid Warden was to go inspect each house in their designated community and to make sure that designated safety supplies were included in each house. Within his collection, there is a handbook containing reports dating May-August 1942 that he wrote based on inspections made in each house within his assigned area. Each report had a list of supplies and a box next to each to check off if the household had that material, and on the back, there was a plan that told the warden the locations of the supplies.

Isidore Zesmer, 1940s

He also became a member of the Citizens Defense Corps in 1943. The Citizens Defense Corps was a team of trained civilian servicemen started by the Office of Civil Defense in Dallas to operate the passive defense for each sector of the Dallas community. Isidore was chosen to be a constituent of the Citizens Defense Corps Dallas-City Council Civilian Defense Council since he fulfilled the necessary requirements in terms of showing patriotism towards his country by signing up to be an Air Raid Warden.

After his term as an Air Raid Warden, on August 21, 1945, he became a life member of the Zionist Organization of America. The Zionist Organization of America, at that time, had a mission to work together with its members to create a legally secure home for the Jews in Palestine. The certificate of Isidore’s lifetime membership states that he has earned all of the privileges of a member according to the organization’s constitution.

Isidore Zesmer owned stores such as Zesmer’s Bootery and Triangle Shoe Manufacturing Co. In Zesmer’s Bootery, he was selling heels for women and boots for both men and women. Triangle Shoe Manufacturing Co. was a shoe factory, and the shoes made in the factory were exported to stores such as Zesmer’s Bootery. Both of his businesses went well until October 24, 1947, when he went out of business due to financial problems.

Even though his business closed, Zesmer was well respected in the community. In May 1951, he was elected as an officer at the Texas Zionist Conference. He was also part of the executive committee for Texas Zionist Association (TZA). Zesmer, his son David, and David’s wife became members of the American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel. He even helped create the Institute of Science in Rehovoth, Israel. Though he helped create the foundation by funding money for the construction, he was not able to go to its inauguration ceremony. On December 24, 1951, he became president of a local branch of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association, which was established as a nondenominational youth organization where social and physical activities were organized and held.

Recognition

As a result of his hard work and commitment towards the Jewish community, he earned recognition and accolades. On December 24, 1951, Zesmer was given a letter acknowledging his distinguished service amongst his fellow citizens for working with the Bonds of the Israel Government to raise $500,000 in the Jewish community and transfer the money to Israel to build up a strong, democratic economy. A tribute dinner related to these honors took place at the Baker Hotel in Dallas, where he received a plaque from the Jewish National Fund (JNF). He earned a certificate from JNF for donating 20 trees to Israel in 1953. He was also invited to the Thousand Dollar Club, an organization that accepts monetary contributions for drives such as the $500,000 Expansion Fund for the Zionist Organization of America (ZOA), and to enlarge youth activities, education, and publication projects, by Abba Hillel Silver. He turned down the offer saying that he was glad to receive the offer, but he never wanted to join a new club. There was also a committee called “Community Honors Zesmer” Committee and a week named after him called “I. Zesmer Bond Week.” Zesmer was included in the Honorary 75th Anniversary Committee on December 27, 1951, the day of his tribute dinner, by the Bonds of the Israel Government, which was established by the Jewish Welfare Federation, for his hard work and devotion to the Jewish community.

Isidore Zesmer, 1950s

On August 31, 1957, a testimonial dinner held at Shearith Israel was conducted in his name for his contribution to the Million Dollar Campaign of 1947 and to the Jewish National Fund. There were letters of appreciation sent to Zesmer from Fred M. Lange (July 22, 1957), Harrison Hastings (September 16, 1957), Leland S. Dupree (August 12, 1957), and Mrs. Milton Tobian (August 29, 1957). The letters expressed each person’s gratitude for Zesmer. During the dinner, he received a plaque stating the name of the village, Naclah Zesmer, in Israel created in his name and the amount of money, which was $30,000, donated to the village.

Jennie Zesmer

Isidore Zesmer was not the only influential person from his family. His wife and children followed his path to lead and serve the community. His wife, Jennie Zesmer, became a school teacher at Royal St. School in 1912 before getting involved with the Hebrew School of Dallas. Mrs. Zesmer contributed to the Jonathan Club, which was established by the Hebrew School of Dallas, by acting in a promotional film that showed her and Al Butler examining pieces of a first aid kit while Scoutmaster and principal of the school, J. Levin, looks on with satisfaction. In the trailer, the first aid kit was a gift from Adolf Weinberger. Jennie also acted as Chairman of the Temporary Camp Committee, beginning in 1942. She cooked food for kids at Camp Bonim and got involved in the PTA for the Hebrew School of Dallas, where she was the President of the PTA for a time.

She was also the regional president of the Women’s Division of Hadassah in Dallas, and on November 18, 1938, she was elected as head at National Hadassah Parley. During her time with the organization, she attended the Minute Conference in 1939 to talk about Palestine’s conditions and how Jewish refugees were pleading for help near the Gaza Strip in Palestine. During the Minute Conference, she invited Rabbi S.A. Tofield to talk about education, the lifeline of Judaism, and democracy. Jennie attended conventions for Hadassah including the first one held at Rice Hotel in Houston, TX (October 17 & 18, 1937), one held in New York City (October 1939), and the last two held in the Texas-Louisiana Region (November 1939 and October 1940).

She also became the Vice President of the Women’s Division of the Jewish Welfare Federation of Dallas. She did a lot of work helping people buy furniture and other necessities for their homes and supported other Jews around the world by requesting donations from the Jewish community. During her time with the Women’s Division, Jennie helped spread the news about donating money to help prevent catastrophes such as one that would occur in early September 1951 that involved tens of thousands of Jews in Palestine who had to be rescued and required $35,000,000 in aid.

In 1941, Mrs. Zesmer became a Parliamentarian of Southwestern Council of Synagogues and Southwestern Conference of Traditional Sisterhoods (SCSSCTS). SCSSCTS is dedicated to preserving the principles and ideals of traditional Judaism in the setting of the American Southwest. Mrs. Zesmer participated in the community by writing and sharing essays and plays about Judaism. One play she wrote was called “The Chanukah Spirit”, and an essay she wrote about Judaism and the Torah was called “Crown of Learning.” She died in November 1944, leaving her children and husband behind to carry out her legacy. A Dallas Chapter of B’nai B’rith Girls (BBG) was named after her – Jennie Zesmer BBG #300 – in recognition of all she did for the Dallas Jewish Community.

Death

Isidore Zesmer remained committed to his community until his death on October 6, 1961, at the age of 73. Before his death, he requested the community not to mourn for him since he wanted them to remember that he is with everyone, and will live on through the minds of everyone in the Jewish community. A letter of tribute was sent out in honor of Isidore Zesmer on November 3, 1961, stating how much the community mourned Zesmer’s death. On October 25, 1962, the Zesmer Sports Field was created in Kfar Silver, Israel in his honor.

Conclusion

Overall, Isidore Zesmer was an influential leader who had a positive impact on the Jewish community. Zesmer fought for education by spreading the message that all Jewish kids should be Jewishly educated, focusing his efforts on Shearith Israel and Hebrew School of Dallas. In addition to focusing on education, he contributed to Jewish organizations, both financially and with his time and attention. Today, Zesmer’s good deads toward his local community and other jews globally still prevail in the minds of Jewish Dallas

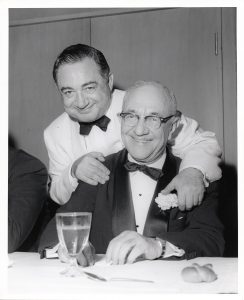

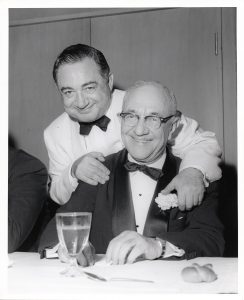

Gala honorning I. Zesmer, undated

Isidore Zesmer Collection

Works Cited

Isidore Zesmer Collection, 1925-1967 and undated, Dallas Jewish Historical Society, Dallas, Texas.

Every single one of us collects–whether it is a conscious habit or not. We may collect stamps, spoons, mezuzahs, Beanie Babies, art, mugs, ticket stubs, Chinese takeout fortunes, or any item we hold an affinity for, or which serves as a memento from an event. Collections may be curated, or formed intentionally, with special thought placed in the acquisition of each new addition—or they can form organically, resulting from a combination of time and proximity.

Every single one of us collects–whether it is a conscious habit or not. We may collect stamps, spoons, mezuzahs, Beanie Babies, art, mugs, ticket stubs, Chinese takeout fortunes, or any item we hold an affinity for, or which serves as a memento from an event. Collections may be curated, or formed intentionally, with special thought placed in the acquisition of each new addition—or they can form organically, resulting from a combination of time and proximity. Ginger, co-founder of the Dallas Jewish Historical Society (DJHS) in 1970, was an undeniable tour de force, an influencer, and a figurehead in the Dallas Jewish community. Not only did she pour her heart into DJHS for decades, she actively participated in several organizations, including (but not limited to) B’nai B’rith Women, Pioneer Women, Women’s ORT, Hadassah, Texas Jewish Historical Society, and the Jewish Federation of Greater Dallas.

Ginger, co-founder of the Dallas Jewish Historical Society (DJHS) in 1970, was an undeniable tour de force, an influencer, and a figurehead in the Dallas Jewish community. Not only did she pour her heart into DJHS for decades, she actively participated in several organizations, including (but not limited to) B’nai B’rith Women, Pioneer Women, Women’s ORT, Hadassah, Texas Jewish Historical Society, and the Jewish Federation of Greater Dallas.

Stuart Rosenfield

Stuart Rosenfield

Recent Comments