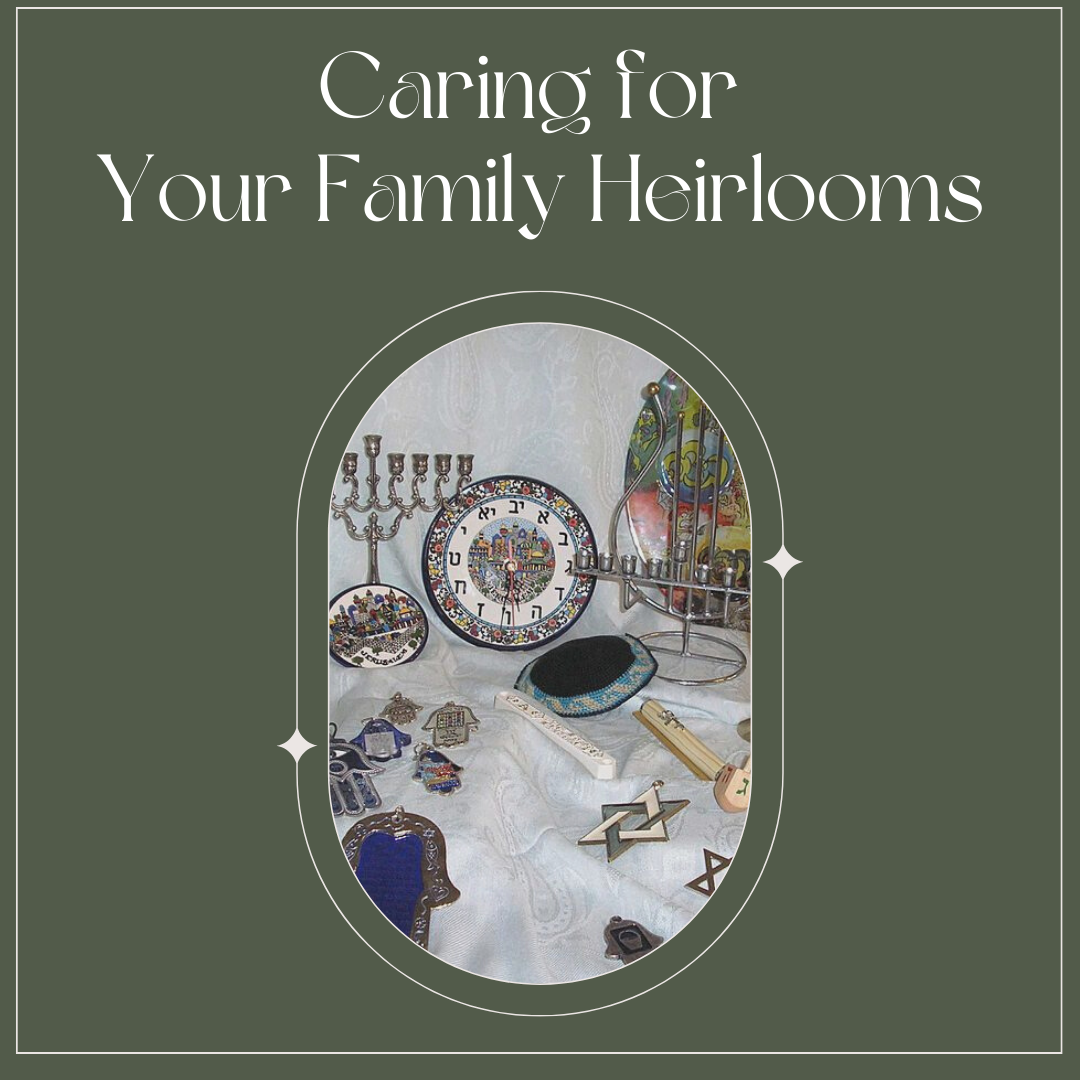

Back for its second iteration, the 2nd Annual Judaica Roadshow included more artifacts, more intrigue, and – if it’s possible – even more heart.

Back for its second iteration, the 2nd Annual Judaica Roadshow included more artifacts, more intrigue, and – if it’s possible – even more heart.

For those unfamiliar with the format, Judaica Roadshow is our spin on the network television series of a similar name. While we mimicked some aspects of the familiar format, we structured our program to fit our community, and include preservation and care advice to promote longevity of the cherished items. The items selected in 2023 and 2024 fell into the following preservation categories: silver/metal alloys, books/paper, oil paintings on canvas, watercolor on paper, glass, glazed ceramic and painted wood.

Read below to learn about how and why these types of objects and materials age the way they do and what you can do to care for them.

Silver and Silver Alloys

Silver tarnishes due to a process called oxidation. Oxidation is caused when an element, in this case silver, reacts with atmospheric compounds, such as (but not limited to) sulfur, on a chemical level. This is what creates the layer of discoloration when silver sits unused for long periods.

When handling silver artifacts, use clean hands, clean cotton gloves or clean nitrile gloves to minimize the transfer of acids and oils on our hands that accelerate oxidation and etching.

There is discourse in the preservation community regarding how and when to clean silver. Our recommendation is to clean silver judiciously. When you clean silver, you are effectively removing a layer of the artifact. Over time, this wear can weaken the artifact, increasing the likelihood of physical damage/alteration and cause loss of detail. It is easier for you, and better for the object, to maintain a cleaned surface than it is to wait for an object to severely tarnish before cleaning. However, if your silver is already tarnished and will likely remain in storage, it may be advisable to leave that stable layer of tarnish in place, especially if details are already obscured due to wear.

Store silver in a cool, dry place where fluctuations in temperature or humidity are minimal. Silver tarnishes more rapidly in hot and damp environments. Package silver in silver cloth, or unbuffered acid-free tissue paper and a polyethylene zip-loc style bag. Silvercloth has particles of silver or other compounds that absorb atmospheric pollutants before they have a chance to interact with the surface of the silver object. Acid-free tissue works in a similar fashion, providing a barrier that will also slow exposure to air and its compounds. Avoid storing in cardboard or other types of plastic, as their inherent composition – the chemicals they are made of – can accelerate and worsen oxidation.

If the silver artifact is on display, place it in a location out of direct light and with consistent temperature and humidity. An air-tight cabinet is ideal, but not always practical. If you wish to keep the item free of tarnish, dust and polish regularly with a soft cotton cloth or polishing cloth while wearing gloves. This will not prevent oxidation, as that is unavoidable, but it will help to slow the process and maintain the item’s luster. One option to protect the piece is to consult a conservator about having the artifact cleaned and coated with an archival lacquer, such as Acryloid B-72 – a long-term, but impermanent solution. You can also purchase activated charcoal and other anti-tarnish inserts that work to absorb harmful pollutants for short periods of time.

It is also important to consider any wood the object is around. Wood should be well-sealed with a varnish that is archival quality, such as polyurethane. Natural compounds in wood, as well as chemicals in stains and some varnishes can accelerate oxidation.

When cleaning silver, if you choose to do so, use a gentle phosphate-free detergent, as phosphate can cause discoloration on the surface of silver objects. To polish, a mildly abrasive paste of baking soda and water is recommended. Gently scrub in circles, rinse well. Dry completely with a soft cloth.

Books

When considering the needs of books, many factors must be considered, including the various materials that make up the pages, binding, and covers, how those materials interact, and how that may impact how a book ages. Books are prone to aging – predominantly discoloration, embrittlement, and weakness is binding materials. The needs of historic books vary based on the composition – the types of materials used to create the book. Leather, paper, board, adhesive, and cotton-based thread are most often used, but you may run into vinyl covers, covers inlaid with metal or even precious/semi-precious stones, or pages made of vellum. The composition of inks varies substantially, as well.

Handle historic and delicate books with clean hands or well-fitting nitrile gloves. Dexterity is important when handling books because pages may be brittle and prone to loss. You may use a mini-spatula or letter opener to help turn pages if the edges are particularly delicate. Always support the spine and never open the book flat on a table. This will accelerate any separation of the binding materials.

Store books away from high heat and fluctuations in humidity, as well as away from places at risk of water damage, such as basements or near pipes. Paper and paper-based materials are hygroscopic, meaning they absorb and release moisture depending on the surrounding environment. This causes changes on the molecular level, weakening pages and binding materials over time. Adhesives are also sensitive to fluctuations and can fail more rapidly when exposed to extremes. Leather, vellum, and parchment can become brittle, or begin to secrete natural emollients when stored improperly, which also increases risk mold, fungus, and other pests, while vinyl can become brittle and flake or break apart easily.

Inks may fade or bleed when exposed to high temperature or humidity. Chemicals in inks, pages or paper-based covers, and those used in leather tanning processes off-gas and often lead to discoloration. This is why the pages of many aged books are yellow or ochre in color. Paper is naturally prone to discoloration and embrittlement as it ages due to chemicals inherent to the materials used in paper production, and aging will accelerate when exposed to additional compounds in inks and binding materials. Overall, books are prone to pests such as (but not limited to) mold and silverfish; moisture makes the environment even more inviting.

If displayed on a bookshelf or similar case, place the book out of direct sunlight. Prolonged exposure to light of any level can cause the cover to fade; bright/direct light will speed up the process. Heat from direct light can also compromise any adhesives and cause pages and covers warp.

Store small and medium books vertically, how you would orient them on a shelf. Store large volumes, especially those with soft covers flat to minimize warping and separation. Particularly delicate volumes can be protected from further damage by storing in specialty phase boxes, or wrapped in archival tissue and then placed in an acid-free box or zip-loc style polyethylene bag.

Watercolor Paintings

Paper is the support of most watercolor paintings, though watercolor is also seen on other materials, such as ivory, bone, vellum, glass, and, wood. We will focus on paper since it is the most common. Paper is inherently sensitive to temperature and humidity fluctuations. Chemicals and compounds in the materials can cause it to discolor and become brittle when exposed to extremes. Paper may also interact with chemicals in pigments, also leading to degradation over time.

Properly cared for, watercolors made with permanent colors on good quality paper are as permanent as any other medium. However, fugitive pigments – pigments that change overtime – especially when exposed to light and heat – will be particularly noticeable in watercolor painting.

Mishandling and mistreatment in storage and display poses the highest risk to watercolor paintings. Paper is naturally delicate, even when durable and of high quality. It is easily damaged and needs to be handled with utmost care – if it cannot be framed it should be stored flat in a supportive portfolio in an acid-free envelope, or in an acid-free folder in a metal filing cabinet if it is small enough, or stored rolled, interleaved with acid-free tissue in an archival tube if it is oversized.

If it can be framed and displayed, it is recommended to display out of direct sunlight, or direct bright light – strive for moderate indirect light. Exposure to light – both for long periods and/or bright, direct light – will accelerate aging and chemical changes (like discoloration and embrittlement) to both the support (paper, usually), and the pigments. One way to mitigate this is to frame the painting in archival materials with UV-filtering acrylic or glass.

Oil Paintings

Every kind of art, every kind of painting will have a unique set of needs. Oil paintings are among the more stable, but there are still steps you can take to ensure longevity. The most common cause of damage to an oil painting is improper handling and storage, but they are also sensitive to other factors in the environment.

Always handle oil paintings by the frame or by the strainer (the support the canvas is stretched around) with two hands on the left and right sides. Never carry with one hand on a single side. Wear gloves or use clean hands if any part of the surface/paint needs to be touched for any reason. If the frame or strainer are unstable (moving at joints when handled) or the canvas is flagging (loose on the strainer), consult a framer or conservator for stabilization.

When considering where to hang an oil painting, factors such as light and humidity levels should be considered. Oil paints themselves are not prone to fading, but they are impacted by the heat direct or bright sunlight and incandescent lights generate, as are their canvas/board and frame. The canvas, board, and frame will also be impacted by fluctuations in humidity, expanding and contracting, which can lead to cracking or delamination (separation of the paint from the canvas or board).

Store oil paintings vertically with the face protected by a plain cotton cloth with the face of the artwork positioned in such a way that no other objects will come in contact with or lean on the face of the painting. If anything leans on canvas, it will lead to stretching, which compromises stability and integrity over time, leading to cracking and loss on the surface. Ideally, paintings will be stored in slip cases, shadow boxes, or crates, depending on the size and value of the piece, as well as storage space.

Consult a conservator when it comes to cleaning oil paintings. The process generally includes solvents that may be harmful in the home environment.

Glass

While glass may be hard to the touch, is actually considered an amorphous solid because of its chemical structure. This can cause historic glass to alter over time due to gravity – it is particularly noticeable in extremely old windows. It’s chemical makeup is also what allows glass to be transparent, and it is also makes it so fragile.

The Canadian Conservation Institute cites, “commonly used raw ingredients for glass include quartz (silica), mixed with sodium (“soda”), potassium (“potash”), or lead as fluxes, and calcium (“lime”), which acts to stabilize the glass. Small amounts of colorants are often used, including iron, copper, cobalt, and manganese. Lead increases the density and improves the optical qualities of glass. The composition of glass, particularly the proportion of silica to fluxes and stabilizers, determines its stability.”

Glass is fairly stable and not at high risk in light, temperature, or humidity extremes; however, those extremes can exacerbate existing condition issues in the composition of the piece over time. Glass of extreme age, or that has been exposed to other stressors (which can be present from the glass-making process), can develop a condition called crizzling.

Crizzled glass has a network of very small cracks on the surface, sometimes invisible to the naked eye. If crizzling worsens, it can lead to delamination (loss) from the surface of the glass and will increase the chances of breakage.

Improper or careless handling is the biggest risk factor to glass objects. When you pick up the item up, do so gently, inspect if for any signs of deterioration, and know where you are going to go with it. Display it somewhere it won’t be likely to be bumped or knocked over. If/when you wish to pack it for storage, wrap it in a soft cloth or tissue paper and store in an appropriately sized box that is labeled with its contents and the words, “fragile, glass.” Do not wear gloves when handling glass, your hands have the grip you need to safely handle glass – unless the glass has a painted or embellished surface. In that case, wear nitrile gloves, which allow for dexterity without transferring oils from your hands onto the object.

Clean pieces in good condition with a mild soap and lukewarm water, taking care when handling and drying. If you suspect your artifact has any crizzling, cracks, separation, or other signs of aging, it is not advised to clean that artifact. If artifacts are painted or have other embellishments, consult a conservator prior to cleaning.

Glazed Ceramic

Ceramics are among the most stable and easily preserved objects in home collections. Their biggest risk factor is physical damage from accidents and improper handling; however, they can be affected by heat, humidity, and moisture.

Most glazed ceramics can be handled without special tools such as gloves, but ensure the object and your hands are dry and free of substances that can make the object slick to reduce the risk of dropping. Always handle with two hands for greater stability when transporting

Some historic and antique glazes include toxic metals or other minerals that can be harmful when handled, so it may be advisable to consult an expert or do personal research to learn about what glazes a producer may have used in a certain timeframe. Generally, these glazes have a luster-type finish, appear to be gilded (this does not include gold-toned details on china), or have very saturated hues. When in doubt, wear gloves, and do not use these vessels for food or beverage.

Over time, ceramic glazes can age and crack, a condition called crazing. Crazing is caused by the natural composition of glazes, as well as exposure to temperature extremes, moisture, and handling. When crazing occurs, more moisture can reach the ceramic body itself, which can lead to further delamination or loss of glazed areas and an interaction called spalling, which is when minerals in the clay body leach to the surface. Oxidation can also occur if iron or other minerals are present in the clay body and exposed to water and air. Moisture in the clay body can also lead to cracking, though cracks are most often caused by extreme fluctuations in temperature and mishandling.

Store or display the object in a place where it is unlikely to be bumped. If your ceramic item is known to be food safe, you can clean with soap and water and dry with a soft cloth. Avoid using anything abrasive, as it can accelerate wear to the glazed surface. If the object is decorative, clean by dusting with a soft cloth and avoid use of water.

Wood

Wood is a hygroscopic material, meaning it absorbed and expels moisture based on its environment. If it is humid, the wood will swell; if it is dry, the wood will release. This can cause warping, embrittlement, cracking, splitting, loss of detail, and loss of functionality (depending on if the piece is functional or decorative). These risks increase if the wood piece has any thin or delicate components. If a piece has been previously repaired, any adhesives or fillers will also be impacted by fluctuations, and may separate from the wood surface over time. Thus, it is advised to store and display wood objects in consistent temperature and relative humidity, approximately 70 degrees +/- a few, and about 50% humidity.

Painted and varnished wood artifacts can pose a complex preservation issue because repeated expansion and contraction and/or warping can case paint and/or varnish layers to separate from the wood surface, leading to cracking and chips. Varnish and paint often discolor with age (yellowing, darkening), as well, this is due to interaction between the varnish or pigments and the chemicals in the wood itself. Plain, untreated wood surfaces will also change in color and fade over time when exposed to light and humidity extremes.

Display wood objects where they will not be splashed or regularly exposed to moisture, and out of direct sunlight.

To store, it will depend on the nature of the object how you will want to store it. If it can be stored in a box, wrap it in acid free tissue and surround it in supportive materials. If it can be laid flat, lay if flat, wrapped in acid-free tissue.

When cleaning natural wood artifacts, use a mild soap and soft cloth to spot clean an area with as little water as possible. Do not use commercial furniture polishes or other chemicals. Rather, use a natural mineral oil to maintain luster and resiliency of the wood without exposing the materials unnecessary chemicals. To clean a painted wood artifact, consult a conservator.

Textiles, Fabric & Garments

Textiles pose a variety of preservation concerns because of the variety of materials, pigments, and other chemicals used during manufacturing. Textiles fall into one of four categories: cellulosic (plant-based – cotton, linen, bamboo, etc.), proteinaceous (derived from animals – silk, wool, fur, feathers), synthetic (lab-created – polyester, spandex, fleece, etc.), and composite (some combination of the other categories). Each of the categories comes with its own set of needs and challenges.

Over time, all categories are prone to physical changes due to gravity, wear/use, tears from accidents, etc. These changes accelerate when exposed to light, as well as temperature and humidity extremes. Pests (such as mold, mildew, moths, silverfish, and rodents) pose particular risk for textiles, especially when stored in dark, warm, and damp environments. It is recommended to store textiles in an environment where you are also comfortable (moderate temperature and humidity – so not your basement or attic – ideally away from water pipes),but protected from light. It is vital to inspect textiles for signs of pests regularly (once or twice a year is a good rule of thumb). Pests are less likely to move in if you in the space moving things around, and if you do come across signs of pest damage, you can minimize its impact and mitigate risk of future damage by checking on them regularly. Along these same lines, allowing for air flow in and around your textiles by storing in cotton bags in spaces that are not jam-packed is also ideal.

Fading, discoloration, and embrittlement due to the chemicals in a textile (either inherent or added), pigments used, and the environment where the textile is kept are also common preservation issues. Some of these changes are unavoidable, but they can be slowed with proper care and storage. As mentioned above, keep textiles out of the light. If you do choose to display, do so in a place that is never in direct sunlight or direct bright light. Shoot for moderate indirect light. Framing behind uv-filtering glass or acrylic is also an option in some cases. Store textiles flat when possible, layered with unbuffered acid-free tissue. Rolled onto an archival tube with acid-free unbuffered tissue paper between the layers is next best. If you must fold, pad the folds with tissue paper, as well. Hanging clothing on well-padded hangers covered in natural cotton is okay. Store in acid-free boxes or covered in natural cotton muslin or Tyvek to keep dust and other atmospheric pollutants (smoke from cigarettes or fireplaces, residue from gas stoves, etc) away. Tears for accidents or mishandling, or holes from use can occur in textiles. These can be stabilized to mitigate futher damage/fraying/unravelling/etc. and often repaired. It is recommended to contact a textile conservator for specifics on how to stabilize delicate historic textiles.

Additional Resources are linked below:

Silver Care – Henry Ford Museum

Caring for Metal Objects – Canadian Conservation Institute

Preserving Books – National Archives

Caring for Oil Paintings – Guardian Fine Art Services

Caring for Paintings – Candaian Conservation Institute

Care for Ceramics and Glass – Candaian Conservation Institute

Ceramics – Western Australian Museum

Caring for Watercolor Paintings

National Park Service – Caring for Wooden Objects

Getty Center – Painted Wood (2)

Quick Tips for Textile Care & Preservation

Guidelines for Textiles & Costumes

As promised, Jessica’s favorite mini-spatulas

Jessica, your presentation today was excellent. Thank you.

If possible, please notify me when the video is available.